Paolo Rossini

Time and Place: Thursday, 01.07., 11:15–11:35, Room 1

Session: History of Science

Background

It is a common view that ideas and viruses share key features such as stickiness, resilience, and contagiousness. A corollary of this view, popularized by such books as Malcom Gladwell’s The Tipping Point (Gladwell 2001), is that epidemic models can also be used to explain “social epidemics” – when ideas and products become popular in an uncontrolled manner. In recent years, epidemiol ogy in general has received great impetus from the rise of network analysis as an independent and interdisciplinary field of inquiry. Ever since its inception, the tools of network analysis have been employed to study the spread of phenomena as diverse as epidemics, wildfires, and earthquakes. Following these developments, this paper will give a concrete example of how network analysis can improve our understanding of the way in which new ideas were circulated throughout history. Tak ing as a case study the “father of modern philosophy” René Descartes (1596-1650), I will show how a network analysis approach sheds new light on the circulation of his ideas across Europe. Building on the assumption that “early modern correspondence provides a unique textual witness to social relations and structures” (Ahnert and Ahnert 2015, 2) I will illustrate how “connectors” (to borrow Gladwell’s words) such as Constantijn and Christiaan Huygens helped Descartes build a reputation by using their correspondence networks to spread the word about him across national and cultural borders.

Methods and Data

My data set consists of the metadata (i.e. sender, recipient, origin, destination, date) and full text of some 20,000 17th-century letters exchanged between correspondents who, for the most part, were born or resided in the Dutch Republic. The temporal and spatial scope of this data set, which was ex tracted from the web application ePistolarium (see Ravenek, Heuvel, and Gerritsen 2017) matches perfectly Descartes’ activities and whereabouts, as the French philosopher spent most of his adult life in the Low Countries. To be sure, the ePistolarium provides structured information about the correspondence of major representatives of the Dutch Golden Age, including Hugo Grotius (7,766 letters), Constantijn Huygens (7,500 letters), and our own Descartes (742 letters). The ePistolarium offers two other advantages. First, the overlap of different correspondence networks warrants the use of centrality measures, which are less suited to the analysis of ego-networks. Second, the ePis tolarium allows the user to search through all the letters and select only those that mention a given person. Capitalizing on these advantages, I proceeded as follows. To begin with, I used the metadata of all the 13,000+ letters dating from the period of Descartes’ correspondence (1619-50) to model a network (hereinafter “A”) in which nodes represented people and edges represented a correspon dence between them. The analysis of A, carried out with Cytoscape, provided me with a list of the nodes with the highest degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality. Then, I used the metadata of the 373 letters mentioning Descartes to model another correspondence net work (hereinafter “B”). To conclude, I used Nodegoat to create two dynamic visualizations – social and geographical – of B.

Findings

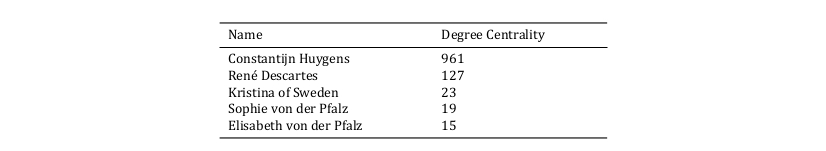

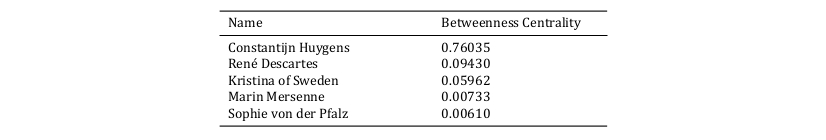

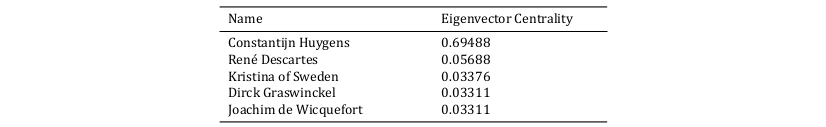

Tables 1, 2, and 3 show that the most central figure in A in terms of the considered metrics was by far the Dutch poet and statesman Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687). Note that the measurements were made on the whole network, though the tables only include Descartes’ first neighbours. In this way, I could focus on Descartes’ ego-network without this affecting centrality measures. The tables also tell us that Descartes was quite close to Huygens as well as to other hubs in the net work, as suggested by his high value of eigenvector centrality. This raises the question, how could Descartes have used his connection with Huygens to his own advantage? We already know that Huy gens helped Descartes on various occasions, for instance by using his political influence to defend Descartes during the so-called Utrecht crisis. But could Huygens have helped Descartes promote his philosophy by turning his correspondence network into a platform to spread the word about the French philosopher?

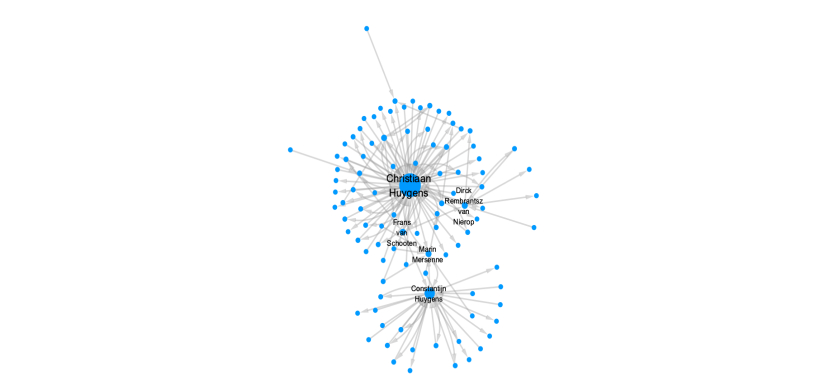

Figure 1 appears to confirm this hypothesis as it shows that Constantijn Huygens was indeed one of the most active nodes in the represented correspondence network, with 23 of his letters mention ing Descartes. However, it was his son, the famous physicist Christiaan Huygens (1629-95), who wrote the highest number of letters in which Descartes was named (126). As a matter of fact, most of Christiaan’s letters were written after Descartes’ death in 1650. Moreover, it must be noted that the entire correspondence of Marin Mersenne (sometimes referred to as “Descartes’ Paris agent”) has not been considered here since the ePistolarium only contains a few letters of him. In the future, I plan to extend the scope of my data set by including the Mersenne data stored in EMLO (Early Mod ern Letters Online) and to assess the information gained from the analysis and visualization of the networks against a close reading of the correspondence. But as it is, Figure 1 reveals the existence of an epistolary community in whose records Descartes’ name occurs very often. Furthermore, a geographical visualization of B (not included here for reasons of space) highlights the transnational and pan-European nature of this community, whose members reside in places as far removed from one another as Sicily, Spain, and Sweden. To my knowledge, this community has been overlooked in the literature, perhaps because the main focus has been on scholars who mentioned Descartes in their treatises rather than in their letters.

References

Ahnert, Ruth, and Sebastian E. Ahnert. 2015. “Protestant Letter Networks in the Reign of Mary I: A Quantitative Approach.” ELH 82 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1353/elh.2015.0000.

Gladwell, Malcolm. 2001. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

Ravenek, Walter, Charles van den Heuvel, and Guido Gerritsen. 2017. “The ePistolarium: Origins and Techniques.” In CLARIN in the Low Countries, edited by Jan Odijk and Arjan van Hessen, ch. 26. London: Ubiquity Press. doi:10.5334/bbi.