Ramona Roller and Frank Schweitzer

Time and Place: Thursday, 01.07., 11:55–12:15, Room 2

Session: Networking Correspondences

The Reformation was a major transformative movement in early modern Europe which overthrew the established clerical order.1 It also promoted social dynamics such as confessionalisation, where religious issues became institutionalised and state-controlled and professionalisation, where people adopted unique professions.2 These social dynamics unfold their effect on the scale of society but they originate from the behavioural patterns of individual people who lived in the 16th century. What do these behavioural patterns look like and how can we capture them are the questions addressed in this work.

We try to capture behavioural patterns by extracting communication patterns of people from their letter correspondences. Let us illustrate some communication patterns taking the example of the Strasbourg re former Martin Bucer. Bucer educated many students from Switzerland in Strasbourg. One of these students, Simon Sulzer, had accused Bucer of withholding an important letter from him.3, 4 This letter was sent from Heinrich Bullinger, the head of the Zurich church, to Bucer. According to Sulzer’s allegations, Bullinger ¨ had asked Bucer in that letter to also forward the letter to Bullinger’s compatriot Sulzer which Bucer had not done. Assuming Sulzer is right, Bucer’s communication behaviour resembles that of a censor, a person who deliberately withholds information from others and ensures that she controls the information flow. Did other reformers also communicate as censors? The first purpose of our study is to identify communication patterns by detecting people with similar communication behaviour. We are interested in whether and why two reformers with similar communication patterns ended up pursuing different or similar lives.

In the case of Bucer, we know from historical records that he did not remain a censor in all of his communication but also adopted other patterns. For example, he acted as a mediator in the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern in 1537.5 This controversy, as many of its sort, dealt with the question of whether during the Lord’s Supper Christ’s presence is real or symbolic. One faction supported the Lutheran view (symbolic) whereas the other faction supported the Zwinglian view (real). Bucer who supported a middle-way tried to reconcile the two factions. The second purpose of our study is to identify changes in the communication behaviour of people over time. We can capture fast changes because letters were exchanged within days whereas other forms of interactions such as contracts or certificates were issued over months or years. We are interested in the extent to which dynamics in communication patterns can explain social dynamics during the Reformation such as confessionalisation or professionalisation.

In this analysis, we call those communication patterns communication roles. Role detection is the process of (1) identifying communication patterns by grouping similar communication behaviours together and (2) labeling these patterns. Our role examples of censor and mediator illustrate that our extracted roles go beyond the binary division of ‘senders’ and ‘recipients’ by capturing more entangled communication pat terns. It is important to distinguish our roles from ‘formal roles’ a concept from sociology6, 7 and also often used in colloquial language. Formal roles are behavioural patterns which are predefined by some authority (e.g. society) and often relate to professions, such as ambassador, merchant, pastor. In contrast, our commu nication roles are a form of informal roles, behavioural patterns which emerge in a specific context through the interplay of people. Although the role concept is a term from modern sociology, we do not try to map specific 21st century roles to a 16th century setting. In contrast, our aim is to extract roles for a specific data set. As a consequence, our extracted roles are not universal and cannot be generalised to other data sets, even if the two data sets are from the same historical period.

Because communication roles are context-specific role detection in networks cannot rely on topological measures alone but also has to pay attention to the multi-dimensional embedding of nodes in the social system.8 Previous research on role detection in networks has used dimensionality-reduction techniques on a pool of node-specific network measures. In order to account for the social context of roles, authors have developed node-specific measures from the content of messages in communication networks,9, 10 and used them together with pure topological measures.11, 12 However, this approach is problematic since message content is not always available in the data. Modeling the social context of roles in different ways may or may not affect role detection. Of specific interest is how network properties on the meso-scale, such as communities, and their relation with individual nodes, e.g. embeddedness of a node within a community, can be use to approximate the social context of roles.

We pose the following research question:

How can we extract context-specific roles of European reformers from their letter correspondence network?

We extract topological and context-specific measures from a directed multi-edge letter correspondence network which is based on 17,000 letters, exchanged between 2,500 people between 1510 and 1575. These data are based on the letter correspondences of seven reformers which were crawled from open source repositories.13, 14 15, 16 17, 18, 19 We use the umbrella term ‘reformers’ to refer to all people in the data independent of whether they supported Protestantism and of the estate (clergy, nobles, bourgeoisie) they belonged to.

As part of our data-preprocessing, we disambiguated the names of all senders and recipients for all seven letter collections together. This step was accomplished by a Historian who used a semi-automated computer programme which we wrote specifically for this purpose. The programme displayed two different names from our data set (e.g. ‘Martin Luther’ and ‘Luther’) and the Historian checked in the respective letters whether these names belonged to the same person or not. For example, we managed to disambiguate ‘Justus Jonas’ who may refer to ‘the Elder’ or ‘the Younger’ who are father and son, respectively. We also identified ‘John Frederick I, Elector of Saxony’ and ‘Duke John Frederick’ to be the same person at two different points in time: before and after the Schmalkaldic War. John Frederick had lost that war and, as a consequence, had to cede his electoral dignity leaving him with the less powerful title of a duke. In addition, we construct a spatial data set of the territories of the Holy Roman Empire, the main domain of power in the 16th century. The attributes of and relations between these territories provide a detailed view on the geo-political situation at that time.

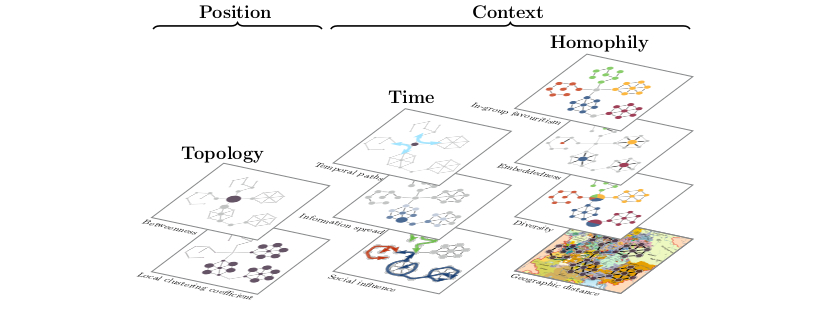

We present a methodology to extract communication patterns from network measures and to provide names to these patterns, our communication roles. We use topological measures to account for the position dependent aspect of a role and time as well as homophily measures to represent the social context. Figure 1 shows how we represent social roles as a multi-layer network. (1) Topological measures correspond to centralities and the size of the local clustering coefficient. (2) Time-dependent measures account for the temporal ordering of links which can be derived by the sending date of the letters. These temporal measures can be used to quantify possible social influence and possible information spread by label propagation and the Infomap algorithm, respectively. (3) Homophily-based measures refer to different kinds of node similarity: structural, spatial and social similarity. Structural similarity considers the formation of communities in the letter correspondence network as well as the structure within and between these communities. Spatial similarity is based on the geographic distance between senders and recipients using the sending and receiving locations of letters in the data. Social similarity infers social attributes of the reformers from the territories they were located in.

This elaborate choice of network measures is necessary for three reasons. First, we require as many topological network measures as possible in our analysis to increase the coverage of communication patterns which we can possibly extract. A large coverage is necessary because we do not know in advance which roles can be extracted from the data set at hand. If we decreased the coverage of network measures we may miss important roles.

Second, we require temporal network measures to capture chronological information flow between senders and recipients via letters. If information flow was only captured by topological measures the chronology of letter correspondences would be distorted and our interpretation of communication patterns may be incorrect.

Third, we require homophily-based measures to account for sociological ingroup-outgroup principles in human interactions. These principles influence human interactions across cultures and historical periods.20 If we did not include homophily-based measures we would falsely ascribe communication patterns to pure dyadic interactions without group effects.

Social Role

Using the example of the censor we can characterise and model her by the following attributes and network measures, respectively.

The Censor

- Non-redundant ¸ large effective network size

- Imbalanced communication behaviour¸ low temporal reciprocity

- Spreads some knowledge ¸ medium temporal out-closeness centrality

- Provides little consistency ¸ low temporal in-closeness centrality

- High control over information flow ¸ high temporal betweenness centrality

We compute each chosen measure for each node in the letter correspondence network. We run a principal component analysis (PCA), a specific type of dimensionality-reduction technique, on our topological and context-specific measures. The PCA allows us to assign several roles to a person, each role being weighted differently. These properties match the real-world findings that people can fulfil different roles at the same time to different extents. This match increases the ecological validity of our analysis. The results of a PCA are interpretable because PCA is a standard approach in statistics whose behaviour is well understood.

We also considered simpler approaches than the combination of Figure 1 and PCA but we came to the conclusion that they do not work. For example, we defined theoretical roles in terms of network measures and included only those ‘relevant’ measures in our analysis. This approach does not work because the theoretical roles are not universal and detected empirical roles are dataset-specific.

Alternatively, we adopted a case study approach where we only analysed the roles of some famous reformers whose biographies and character traits are well studied. This approach does not work because these case studies do not capture large-scale social dynamics and only allow us to study something we already know, namely the behavioural patterns of famous reformers. In contrast, we are interested in network effects and the unknown communication patterns of lesser-known reformers.

Last, we used unsupervised clustering to group nodes according to their values on chosen network mea sures. Nodes in the same cluster would be similar in terms of network measures and be assigned the same role. This approach does not work because it does not control for multicollinearity between the network measures. As a consequence, network measures, which measure similar aspects of comunication behaviour in the data set at hand, would have a larger impact on the clustering result than measures which account for only one communication aspect.

Our analysis enables us to extract the multi-dimensional nature of people’s communication roles and changes thereof.

Footnotes

1. Thomas Kaufmann, Erlöste und Verdammte. Eine Geschichte der Reformation, 2nd ed. (München: C.H.Beck, 2017).

2. Christoph Strohm, Theologenbriefwechsel im Sudwesten des Reichs in der Frühen Neuzeit (1550- 1620) (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag WINTER, 2017).

3. Amy Burnett, “The Myth of the Swiss Lutherans: Martin Bucer and the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern,” Zwingliana777 32 (2005): 45–70.

4. Nelson Amy Burnett, “Generational Conflict in the Late Reformation: The Basel Paroxysm,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 32 (2001): 219–244.

5. Burnett, “The Myth of the Swiss Lutherans: Martin Bucer and the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern.”

6. Talcott Parsons, The Social System (London: Routledge, 1951).

7. Kenneth D. Benne and Paul Sheats, “Functional Roles of Group Members,” Social Issues 4, no. 2 (1948): 41–49.

8. Eric Gleave et al., “A Conceptual and Operational Definition of ‘Social Role’ in Online Community,” Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS, 2009, 1–11.

9. Lamya Benamar, Christine Balague, and Mohamad Ghassany, “The Identification and Influence of Social Roles in a Social Media Product Community,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22, no. 6 (2017): 337–362.

10. Johann Fuller et al., “User roles and contributions in innovation-contest communities,” Journal of Management Information Systems 31, no. 1 (2014): 273–308.

11. Keith Henderson et al., “RolX: Structural Role Extraction & Mining in Large Graphs,” Proceedings of the 18th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining – KDD ’12, 2012, 1231–1239.

12. Ryan A. Rossi and Nesreen K. Ahmed, “Role Discovery in Networks,” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engi neering 27, no. 4 (2015): 1112–1131.

13. ProQuest-LLC, “Luthers Werke on the World Wide Web,” 2015, accessed May 17, 2019, http://luther.chadwyck.co.uk/.

14. Christine Mundhenk, “Melanchthons Briefwechsel – Regesten online,” 2019, accessed May 17, 2019, https://www.haw.uni-heidelberg.de/forschung/forschungsstellen/melanchthon/mbw-online.de.html.

15. Reinhard Bodenmann, “Heinrich Bullinger’s Correspondence,” 2016, accessed May 17, 2019, http://www.arpa-docs.ch/SedServer/SedWEB.cgi?fld_41a=&fld_30b=&fld_41c=&fld_30c=&fld_41e=&search=&range=&Alias=Briefe&Lng=0&first=0&session=0&awidth=1440&aheight=769&PrjName=Bullinger+-+Briefwechsel.

16. Christian Moser, “Huldreich Zwinglis samtliche Werke,” 2016, accessed May 17, 2019, http://www.irg.uzh.ch/stati/zwingli-briefe/?n=Main.Overview.

17. Reinhold Friedrich, “Bucer Briefkorrespondenz,” 2018, accessed May 17, 2019, https://www.theologie.fau.de/lehrstuhl-kirchengeschichte-ii-neuere-kirchengeschichte/bucer-forschungsstelle/.

18. Thomas Kaufmann, “Kritische Gesamtausgabe der Schriften und Briefe Andreas Bodensteins von Karlstadt, Teil I (1507–1518),” 2012, accessed May 17, 2019, http://diglib.hab.de/edoc/ed000216/start.html.

19. Martin Wallraff, “Erschließung des Briefwechsels von Oswald Myconius,” 2016, accessed May 17, 2019, https://myconius.unibas.ch/briefdb.html.

20. Miller McPherson, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James M Cook, “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks,” Annual Review of Sociology 47 (2001): 415–444.

References

Benamar, Lamya, Christine Balague, and Mohamad Ghassany. “The Identification and Influence of Social ´ Roles in a Social Media Product Community.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22, no. 6 (2017): 337–362.

Benne, Kenneth D., and Paul Sheats. “Functional Roles of Group Members.” Social Issues 4, no. 2 (1948): 41–49.

Bodenmann, Reinhard. “Heinrich Bullinger’s Correspondence.” 2016. Accessed May 17, 2019. http://www.arpa-docs.ch/SedServer/SedWEB.cgi?fld_41a=&fld_30b=&fld_41c=&fld_30c=&fld_41e=&search=&range=&Alias=Briefe&Lng=0&first=0&session=0&awidth=1440&aheight= 769&PrjName=Bullinger+-+Briefwechsel.

Burnett, Amy. “The Myth of the Swiss Lutherans: Martin Bucer and the Eucharistic Controversy in Bern.” Zwingliana777 32 (2005): 45–70.

Burnett, Nelson Amy. “Generational Conflict in the Late Reformation: The Basel Paroxysm.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 32 (2001): 219–244.

Friedrich, Reinhold. “Bucer Briefkorrespondenz.” 2018. Accessed May 17, 2019. https://www.theologie.fau.de/lehrstuhl-kirchengeschichte-ii-neuere-kirchengeschichte/bucer-forschungsstelle/ .

Fuller, Johann, Katja Hutter, Julia Hautz, and Kurt Matzler. “User roles and contributions in innovation- ¨ contest communities.” Journal of Management Information Systems 31, no. 1 (2014): 273–308.

Gleave, Eric, Howard T. Welser, Thomas M. Lento, and Marc A. Smith. “A Conceptual and Operational Definition of ‘Social Role’ in Online Community.” Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, HICSS, 2009, 1–11.

Henderson, Keith, Brian Gallagher, Tina Eliassi-Rad, Hanghang Tong, Sugato Basu, Leman Akoglu, Danai Koutra, Christos Faloutsos, and Lei Li. “RolX: Structural Role Extraction & Mining in Large Graphs.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining – KDD ’12, 2012, 1231–1239.

Kaufmann, Thomas. Erlöste und Verdammte. Eine Geschichte der Reformation, 2nd ed. München: C.H.Beck, 2017.

“Kritische Gesamtausgabe der Schriften und Briefe Andreas Bodensteins von Karlstadt, Teil I (1507–1518).” 2012. Accessed May 17, 2019. http://diglib.hab.de/edoc/ed000216/start.html.

McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James M Cook. “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Net works.” Annual Review of Sociology 47 (2001): 415–444.

Moser, Christian. “Huldreich Zwinglis samtliche Werke.” 2016. Accessed May 17, 2019. http://www.irg.uzh.ch/static/zwingli-briefe/?n=Main.Overview.

Mundhenk, Christine. “Melanchthons Briefwechsel – Regesten online.” 2019. Accessed May 17, 2019. https://www.haw.uni-heidelberg.de/forschung/forschungsstellen/melanchthon/mbw-online.de.html.

Parsons, Talcott. The Social System. London: Routledge, 1951.

ProQuest-LLC. “Luthers Werke on the World Wide Web.” 2015. Accessed May 17, 2019. http://luther.chadwyck.co.uk/.

Rossi, Ryan A., and Nesreen K. Ahmed. “Role Discovery in Networks.” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 27, no. 4 (2015): 1112–1131.

Strohm, Christoph. Theologenbriefwechsel im Südwesten des Reichs in der Frühen Neuzeit (1550- 1620). Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag WINTER, 2017.

Wallraff, Martin. “Erschließung des Briefwechsels von Oswald Myconius.” 2016. Accessed May 17, 2019. https://myconius.unibas.ch/briefdb.html.