Ana L. C. Bazzan, Silvio Renato Dahmen, Sandra Denise Prado, Máirín MacCarron, Julia Hillner and Ulriika Vihervalli

Time and Place: Friday, 02.07., 12:10–12:30, Room 1

Session: Data and Methodology

Keywords: Robustness of networks; early medieval history; ecclesiastical history

Background

Techniques stemming from the theory of social networks are increasingly being used as quantitative tools with which one may analyse and quantify interpersonal relationships. In particular, historians are employing them aiming at gaining new insights in several case studies (Gould, 2003).

A social network or a graph G is formally defined as G = (N; L), where N is the set of nodes (the actors in the network), and L is the set of links. A link is a connection (or interaction) of any sort between two nodes. There are many measures that quantify the structure of the network and the importance of nodes in a network (see Costa et al. (2007)). One of these is the degree centrality, which measures how many direct connections a node has. Extracting a network from a textual source is a key step in this quantitative process. If this step is not accomplished carefully, then it might be that the insights gained from analysing the structure and other characteristics of the network are flawed or at least partially invalid.

Methods and Data

In this work, we investigate the robustness of networks to mistakes arising in data extraction from textual sources. Specifically, we take networks that were manually compiled— considered golden standards—and insert, with a certain probability, noise of three types: (i) removal, (ii) addition, and (iii) rewiring of connections. Removal of connections aims at investigating what happens if they are missed during the data extraction; the second relates to extra connections being accidentally inserted; the third refers to the human compiler making mistakes such as connecting node A to C, instead of the expected connection from A to B. We then compare the results for the original network to those for the perturbed network. For this experiment, we use early medieval texts in which the role of women as connectors is being investigated within the project ‘Women, Conflict and Peace: Gendered Networks in Early Medieval Narratives’. Among them, we cite Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History, Stephen’s Life of Wilfrid, Baudonivia’s Life of Radegund, and Venantius Fortunatus’ Life of Radegund.

In that project, data from early medieval texts were extracted. These texts date from the fourth to the eighth centuries and have survived in manuscripts. These have later been edited into volume compilations in the original language – Koine Greek and Latin. The data compilers used the edited Greek or Latin volumes, working through the narrative, using their expertise of the language in question and of the historical context of the work to record every active character and any interactions they have. Regarding these, the historian experts have themselves developed a data model of 21 categories. Identity of characters, names, dates, genealogies, etc. were all double checked. While the primary material is sometimes straightforward, this is not always the case.

Sometimes actors and their links in the text can take some effort to establish. To handle such difficult parts, the compilers held several meetings and discussed them all, especially in what regards where certain interactions fell within the 21 categories of interactions. Each interaction recorded is thus the outcome of not only close reading of a text, but the data harvesting process involves numerous steps, checks and discussions by experts. The database also undergoes continuous quality checks to ensure the accuracy of the thousands of entries and the even more numerous links between them, verifying that links are made correctly and between the right people. This work was done by all project members to ensure consistency between databases, maintaining the high quality and accuracy of the data, which will go on to enable comparisons between different databases and their networks. Hence, the historians assess the quality of the collected databases as extremely good, with data being very accurate.

As mentioned, these texts were used to draw conclusions about the role of female actors in the network. For instance, in Prado et al. (2020), the text by Bede was used to investigate communicability of various nodes. One conclusion is that two women were fairly relevant: Eanfled, a former queen of Northumbria, and Hild, abbess of Whitby. Regarding Venantius’ Radegund, one important characteristic of the network is the high number of women (nearly 50%). The other texts are providing further interesting insights too (under investigation). Thus, one may ask how such conclusions would change if each network were not carefully extracted from the textual sources.

To investigate this, we have devised the aforementioned robustness measures. We have perturbed those networks in order to artificially remove, add, or rewire connections with varying probability. For instance, 1% of connections can be changed. We then perform two types of comparisons, with results as follows.

Findings

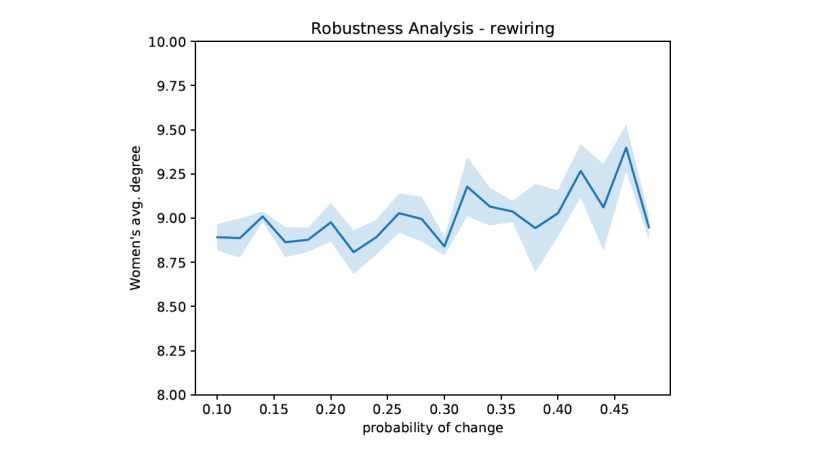

The first type of comparison refers to the average degree of women, i.e., how much the degree of all women in each network has changed. Here, results show that noise of the type (iii), i.e., making the wrong connection between two nodes in the network—no matter if men or women— is less likely to affect the overall conclusion(s), as seen in Figure 1. However, the other two types of errors that are failing to include connections that in fact would exist, or adding connections that in fact would not be present, may affect the drawing of conclusions since they change the degree of women.

The second type of comparison regards the position of key actors in the ranking of women. Here we investigated if the most relevant women would change their position in the ranking of degree centrality. The main conclusion so far is that the ranking of women is resilient to those perturbations.

References

Costa, L. da. F., F. A. Rodrigues, G. Travieso, and P. R. V. Boas (2007). Characterization of complex networks: A survey of measurements. Advances in Physics 56(1), 167–242. Gould, R. V. (2003). USES OF NETWORK TOOLS IN COMPARATIVE HISTORICAL RESEARCH, pp. 241—-269. Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prado, S. D., S. R. Dahmen, A. L. C. Bazzan, M. MacCarron, and J. Hillner (2020). Gendered networks and communicability in medieval historical narratives. (available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.01396).