Song Chen

Place and time: Thursday, 01.07., 15:25–15:45, Room 2

Session: Biographies and Careers in China

Keywords: Chinese history; pre-modern histor; political elite; kinship networks; modularity analysis; core-periphery analysis; regional clustering

Background

The Song dynasty (960–1279) marked a moment of profound transformation from the first and second millennium in the history of imperial China. By the early Song, north China—the traditional heartland of the Chinese civilization—was finally overtaken by south China in its agricultural output, commercial development, and its share of the total population. The accumulation of new wealth, coupled with the spread of the printing technology, made educational resources more widely accessible. In response to these developments, the Song court from the early eleventh century implemented a series of reforms on its civil service examination system and built an empire-wide network of government-sponsored schools. These developments effectively undermined the capital elite’s monopoly over political power. From the mid-eleventh century, an increasing number of men entered government service from outside the capital and especially from south China.

As the officials hailed from a wide area of the Song empire, what impact did this have on their relationship with each other? Did they form a closely-knit endogamous network? How did the structure of their networks change?

Methods and Data

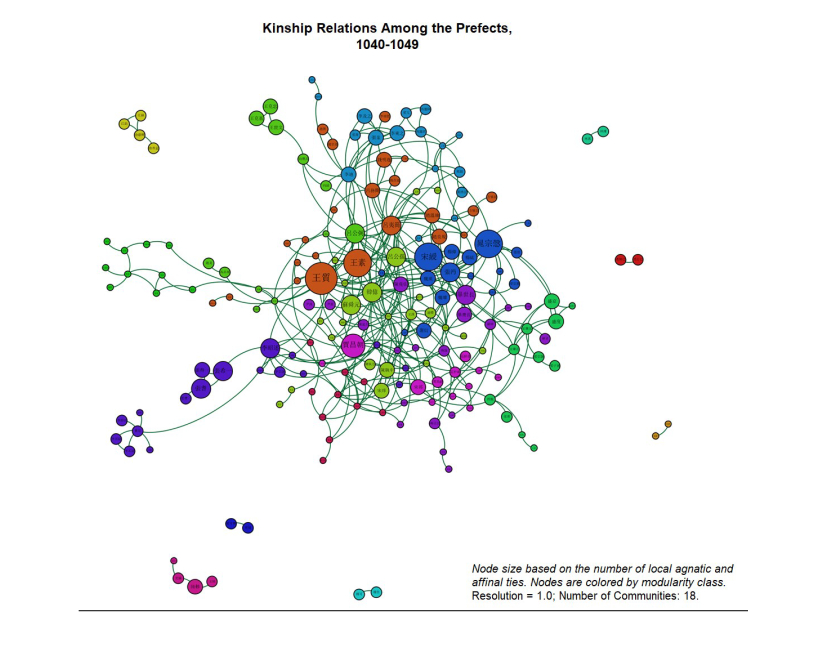

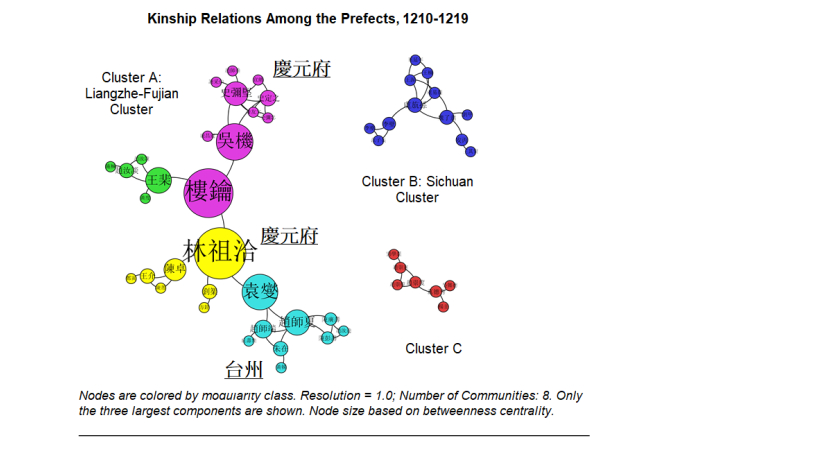

This article explores the above questions by analyzing the kinship networks of prefectural governors who formed the backbone of the Song territorial administration. These prefects, numbering two to three hundred in any year of the period, were responsible for local order and taxation and had direct reporting relationship to the court. Since those who held office between 1040 and 1049 and between 1210 and 1219 are best documented in historical sources, this article compares the kinship networks of these two cohorts of prefects. The 1040s marked the beginning of the expansion of the civil service examination system, and the 1210s was towards the end of the Song dynasty before the Mongols launched their attacks in 1235. A comparison between these two decades, therefore, allows us to understand how the networks of Song officials evolved after the examination system expanded.

The primary data source for this study is the China Biographical Database (CBDB), a freely accessible relational database with biographical information about approximately 427,000 individuals as of April 2019, primarily from the 7th through 19th centuries. The CBDB has recently digitalized the dated rosters of Song-dynasty prefects compiled by historian Li Zhiliang and added data on kinship relations, among others, from other sources. This supplemented by my own database built from a nearly exhaustive collection of funerary biographies on men and women from the Sichuan region during the Song period to compensate for the notable data lacuna on the Sichuan region in Li Zhiliang’s compilations.

This study defines a kinship relation as a reasonably close one if it involves no more than two marriages and no more than two units of collateral distance. It also defines “marriage” broadly as any kinship relation across patrilineal descent groups. Since this study looks only at kinship relations within each cohort of prefects, most of the kinship relations used in the analysis are by nature between persons who were either of the same generation or removed by only one generation. Only a small number of relations are between men who were two generations. Kinship relations that meet the above criteria are found for 211 prefects (out of a total of 511) in the 1040s cohort and 118 prefects (out of a total of 534) in the 1210s cohort.

I have published an earlier study of these two cohorts of prefects as a book chapter in State Power in China, 900–1325. In that study, I looked at the geographic origins of these prefects and the geographic pattern of their appointments. I also conducted a preliminary study of their kinship networks using the metrics of E-I Index and k-core analysis.

This article looks at the kinship networks of both cohorts of prefects in great depths. Three methods are employed to reveal the structural properties of the two networks. First, I have conducted modularity analysis to examine whether each network may be divided into clusters that formed along regional lines. Second, I have conducted core-periphery analysis to detect whether each network exhibits a clear core-periphery structure and who constituted the core of a network. Third, each person-to-person network is transformed into a place-to-place network to reveal the spatial pattern of the network structure.

Findings

My earlier study, based on E-I Index and k-core analysis and published in 2016, reveals that the 1040s prefects are much more cohesive than their 1210s counterparts. Nearly 40% of the prefects in the 1040s (i.e., nearly all of those for whom we have kinship data) ended up in one big component, whereas only less than a quarter of all known prefects from the 1210s, had agnatic or affinal ties with one another. I have also shown, with E-I Index calculations, a notable tendency toward regional clustering in the 1210s compared to the 1040s.

My present study, using modularity and core-periphery analysis, provides more analytical support for these findings. I show that core-periphery analysis is more revealing about the 1040s kinship network, whereas modularity analysis is more effective for the 1210s network. This betokens a structural shift between these networks: whereas the kinship network of prefects in the 1040s exhibits a clear core-periphery structure, with the capital elite dominating the core, that in the 1210s do not have a clear core but instead fragments into two big regional clusters centered on Sichuan and the Southeast Coast respectively. My study also shows that for the 1210s cohort, the Southeast Coast cluster also exhibits a tendency to cluster along prefectural lines.

Network Graphs from the Present Study: