Diane Harris-Cline and Eleni Hasaki

Time and Place: Thursday, 01.07., 13:50–14:10, Room 2

Session: Networks and Cultural Objects

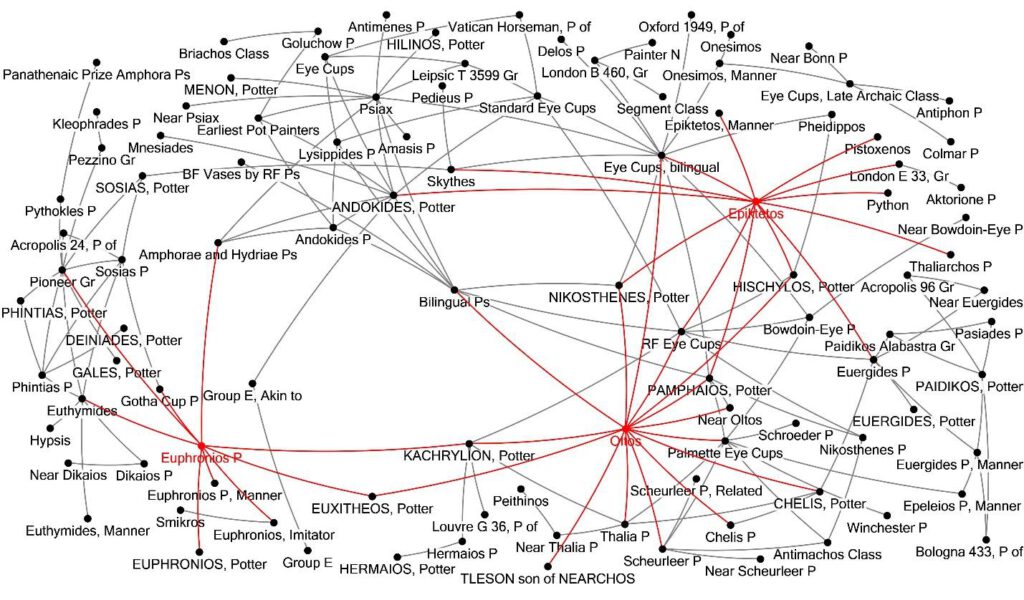

Background: Historians and archaeologists have used the rich imagery on the Athenian pottery of the Archaic and Classical times to study themes such as gender, identity, social status, ritual behavior, cultural memory, and literacy. Potters and painters of Greek pottery shared techniques, styles, and themes or subjects, which art historians have documented extensively. When we notice similarities in technique, style, or iconography, we see these as evidence of social interactions. We have been using social network analysis to map the relationships, which scholars of ancient art have been diligently working on for decades. Drawing on methods established for identifying “schools” of Renaissance painters, one expert in particular named John Beazley wrote catalogues of Athenian potters and painters in his five books totaling over 3,000 pages, which he published between 1956 and 1971. Beazley tackled separately the potters working in the traditional Black-figure technique from those working in the innovative Red-figure technique (Fig. 1). These stylistic ties between artists have been foundational in understanding how the Athenian ceramic industry developed and functioned. Our mapping of these relationships brings to life the archaeological data we have for studying these communities, namely the physical remains of the potters’ work spaces and their surviving technological apparatus, such as potters’ wheels and kilns (Hasaki, web).

From around 520 to 500 BCE, the potters made a remarkable transition from a traditional technique, Black-figure, to a new one, Red-figure. In this case we have an opportunity to witness the diffusion of innovation through the Athenian potters’ quarter. Surprisingly, using social network analysis to analyze this diffusion had not yet been done. We compare how the network of Black-figure relates to the Red-figure. Through social network analysis, we investigate the connectedness in these potters’ networks and we focus on how their craft and business partnerships informed their technical and artistic decisions to either maintain traditional practices or to embrace innovation.

Methodology: This project uses social network analysis software (NodeXL) to visualize connections between the artists, and identify clusters which might be identified as communities of practice. For the field of classical archaeology, this approach is experimental and contributes to the postmodern reframing of ties traditionally based on ancient written sources or modern art historical methods. Our current work, supported by a Digital Humanities NEH grant (USA), is called the Social Networks of Athenian Potters Project (SNAP; snap.sbs.arizona.edu; @AthenianPotters). We are mapping for the first time the potters in Archaic and Classical Athens (600−450 BCE). Ties among potters are based on stylistic relationships that connect potters to each other through a variety of social ties: a potter can have a pupil, a follower, an imitator, or a group of companions. In the sociograms we generate, we study how a potter’s position in the network enhances our understanding both of the significant role of individuals within their social networks, and how social networks of potters cluster into groups on a continuum from conservative and working in a traditional practice versus the pioneering experimental artists. Our SNAP project publications (Cline and Hasaki 2019; Hasaki and Cline 2020) were the first to visualize, calculate, and evaluate the network and show these associations and interconnections. Our proof of concept was to take the entire text of Beazley’s 850-page book on Black-figure potters to produce a sociogram of 710 nodes and 863 ties. This method of analysis provided an entirely new perspective from the traditional vase painting scholarship based on writing catalogues of individual painters and potters in linear form, or making databases which keep interrelationships hidden or do not enable relational searches (Fig. 1). In this paper we present our results from our new study of the Red-Figure communities.

Findings: Once we began to analyze our networks of Red-figure artists, we worked to contextualize them in their wider networks. Having identified some innovators and early adopters through tracing paths across the network, and studying those with the highest betweenness centrality, we can assert that social network analysis of our craft communities can:

a) offer a model to scholars working on a wide spectrum of communities of artists in past and recent cultures, to highlight the social level and connectivity of these influential groups to their peers and their contemporaries.

b) generate interest in developing SNA projects focusing on different craft communities, such as communities of sculptors or temple builders, to promote cross-craft comparison. Scholars of economic history are becoming keenly interested in small business and craft communities for which little written evidence exists, and the potters’ quarter in Athens is a prime example. Building a critical mass of social networks of communities of practice across crafts will move forward our understanding of ancient Greek economic history.

c) Social networks can be used to evaluate and fill in the gaps for the methodological problems linked to the nature of the sparse archaeological and literary evidence for craft communities of pottery workers.

The range of themes for continued research in the study of the social networks of Athenian potters include the diffusion of innovation, apprenticeship, knowledge transfer, visual propaganda, political patronage of artists, and trade.

Bibliography

Cline, D.H. and E. Hasaki. 2019. “The Connected World of Potters in Ancient Athens: Collaborations, Connoisseurship and Social Network Analysis.” Harvard Center for Hellenic Studies CHS Research Bulletin 7. 2019. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:ClineD_and_HasakiE.The_Connected_World_of_Potters.2019.

Hasaki, E. and Cline, D. H. 2020. “Social Network Analysis and Connoisseurship in the Study of Athenian Potters’ Communities.” In Reconstructing Scales of Production in the Ancient Greek World: Producers, Processes, Products, People, edited by Eleni Hasaki and Martin Bentz, 59–80. Propylaeum. https://doi.org/10.11588/PROPYLAEUM.639

Hasaki, E., ed. web. WebAtlas of Ceramic Kilns in Ancient Greece. Accessed 9 January 2021. https://atlasgreekkilns.arizona.edu/